The Ethical Implications of AI in Warfare and Defence: A Comprehensive Perspective

The military AI market is projected to reach $11.6 billion by 2026, signalling a shift from experimental capability to core strategic infrastructure. [1] This expansion demands a robust examination of the ethical and legal frameworks governing autonomous force.

This exploration assesses the intersection of autonomous systems and the ethical imperatives of modern combat, focusing on the shifting landscape of international accountability. A comprehensive exploration of one of the most pressing issues of our time.

Last Updated December 2025

The Rise of AI in Military Applications

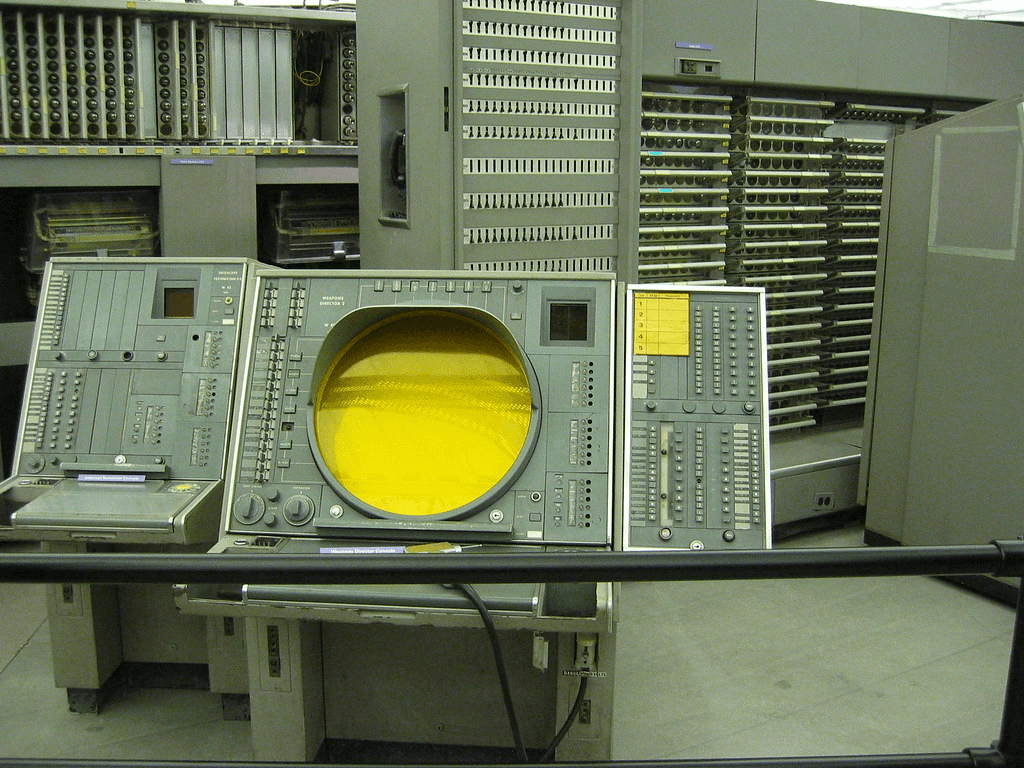

While contemporary discourse focuses on Generative AI, military automation is not a novel phenomenon; it has its roots in the 1950s-era SAGE system, which established the precedent for computer-aided coordination of North American air defenses. The SAGE (Semi-Automatic Ground Environment) system, was one of the earliest examples of AI in military applications [2].

Contemporary military applications have transitioned from coordination (as seen in the SAGE system) to distributed algorithmic agency, including pattern-driven predictive logistics and real-time kinetic threat detection. The current state of AI in defence is represents a paradigm shift in kinetic capability. We’re talking about systems that can:

- Predict enemy movements using pattern recognition and big data analysis

- Optimize supply chains and logistics for military operations

- Enhance cybersecurity through real-time threat detection and response

- Improve target recognition and tracking in complex environments

- Assist in mission planning and strategic decision-making

The United States, China, and Russia are leading this AI arms race, with the UK not far behind.

The Pentagon’s CDAO (Chief Digital and Artificial Intelligence Office) is spearheading the U.S. military’s AI efforts, while China’s 2017 “New Generation Artificial Intelligence Development Plan” outlines their ambitions to become the world leader in AI by 2030 [3]. Russia, not to be left behind, has been investing heavily in AI-powered autonomous weapons systems.

But it’s not just the usual suspects in this high-tech arms race. Israel, for instance, has been punching above its weight in military AI, particularly in the realm of drone technology and cybersecurity. And let’s not forget about the European Union, which has been grappling with how to approach military AI while adhering to its ethical principles.

Potential Benefits of AI in Warfare and Defence

The integration of AI into military theater offers significant operational advantages, specifically in enhancing decision-making latency and providing real-time situational awareness via systems like the U.S. Army’s ATR-MCAS.

- Enhanced decision-making: AI can process vast amounts of data in seconds, helping military leaders make more informed decisions. These systems offer a force multiplier effect, providing a level of computational synthesis previously unavailable to human command structures. For example, the U.S. Army’s Aided Threat Recognition from Mobile Cooperative and Autonomous Sensors (ATR-MCAS) system uses AI to analyse data from multiple sensors, providing soldiers with real-time threat assessments [4].

- Reduced human casualties: Autonomous systems can replace humans in dangerous situations. Imagine sending a robot into a minefield. I’d certainly prefer that! The Israeli-made Harpy drone, for instance, can loiter over a battlefield and attack radar systems without risking human lives [5].

- Improved cybersecurity: AI can detect and respond to cyber threats faster than any human. The UK’s National Cyber Security Centre has been leveraging AI to bolster the country’s cyber defences against state-sponsored attacks [6].

- Enhanced situational awareness: AI-powered systems can provide a more comprehensive and accurate picture of the battlefield. The U.S. Army’s Integrated Visual Augmentation System (IVAS) uses AI to provide soldiers with real-time information about their surroundings [7].

- Predictive maintenance: AI can predict when military equipment needs maintenance, reducing downtime and costs. The Royal Air Force has been using AI to predict maintenance needs for its fleet of Typhoon fighter jets [8].

- Improved training: AI-powered simulations can provide more realistic and adaptive training scenarios for military personnel. The U.S. Army’s Synthetic Training Environment (STE) uses AI to create complex, multi-domain training simulations [9].

While these benefits are indeed impressive, they come with a host of ethical concerns that would make even the most seasoned philosopher scratch their head.

Ethical Concerns and Challenges

The deployment of military AI introduces multifaceted legal challenges, primarily regarding the erosion of human agency in kinetic decisions.

- Autonomous weapons: The idea of machines deciding who lives and dies presents a fundamental challenge to the sanctity of human agency. The ethical implications of Lethal Autonomous Weapon Systems (LAWS) have been a hot topic at the United Nations Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons (CCW) [10].

- Accountability: When an AI-driven system makes a mistake, who do we blame? The programmer? The military commander? The machine itself? It’s a philosophical puzzle that would make even Bertrand Russell scratch his head. The concept of “meaningful human control” has been proposed as a potential solution, but its implementation remains a challenge [11].

- AI arms race: As countries rush to develop the most advanced AI weapons, we risk destabilizing global peace. It’s like the Cold War, but with computers instead of nukes. The risk of escalation and the potential for AI systems to interact in unpredictable ways during conflicts are major concerns [12].

- Bias and fairness: AI systems can inherit and amplify human biases, potentially leading to unfair targeting or decision-making in military contexts. A study by the UN Institute for Disarmament Research highlighted the risks of bias in AI-powered military systems [13].

- Hacking and vulnerability: AI systems, like any technology, can be hacked or manipulated. The consequences in a military context could be catastrophic. The potential for adversarial attacks on AI systems in warfare scenarios is a growing concern among cybersecurity experts [14].

- Ethical decision-making: Can AI systems be programmed to make ethical decisions in complex, real-world scenarios? The trolley problem, a classic ethical thought experiment, becomes all too real when applied to autonomous weapons [15].

- Proliferation and asymmetric warfare: As AI technology becomes more accessible, there’s a risk of it falling into the hands of non-state actors or being used in asymmetric warfare. The democratization of AI could lead to new forms of terrorism and unconventional warfare [16].

- Impact on military culture and human skills: As AI takes over more military functions, there’s a risk of deskilling human personnel and changing military culture in unforeseen ways. The Royal United Services Institute has warned about the potential loss of traditional military skills in an AI-dominated environment [17].

The Debate on Lethal Autonomous Weapon Systems (LAWS)

The debate surrounding Lethal Autonomous Weapon Systems (LAWS) has reached a critical juncture in international diplomacy. While the GGE LAWS continues to move incrementally, UNGA Resolution L.41 (2025) represents a shift toward multilateral regulation. On one hand, proponents argue that these systems could reduce human error and bias in warfare. They contend that AI-powered weapons could make more precise and rational decisions, potentially reducing civilian casualties [18].

On the other hand, critics worry about the lack of human judgment in life-or-death decisions. The “Stop Killer Robots” campaign, supported by over 180 non-governmental organisations, argues that delegating the decision to take human life to machines crosses a fundamental moral line [19].

The international community is trying to get a handle on this issue. The UN Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons has been discussing LAWS since 2014, but progress within the UN CCW framework remains incremental. However, the adoption of UNGA Resolution L.41 in November 2025 marks a definitive shift toward a multilateral approach to autonomous weapon systems. [20]. The main challenges include:

- Defining autonomy: There’s no universally accepted definition of what constitutes an autonomous weapon system.

- Verification and compliance: How can we ensure countries are complying with any regulations on LAWS?

- Dual-use technology: Many AI technologies have both civilian and military applications, making regulation complex.

- National security concerns: Some countries are reluctant to limit their development of LAWS, citing national security.

Meanwhile, tech companies have found themselves in the crosshairs of this debate. Google faced a significant employee backlash over its involvement in Project Maven, a U.S. Department of Defense AI initiative, ultimately leading to the company’s decision not to renew the contract [21]. Similarly, Microsoft employees protested the company’s $480 million contract to supply HoloLens augmented reality headsets to the U.S. Army [22].

These corporate controversies highlight the ethical dilemmas faced by tech workers and the growing intersection between the tech industry and military applications of AI.

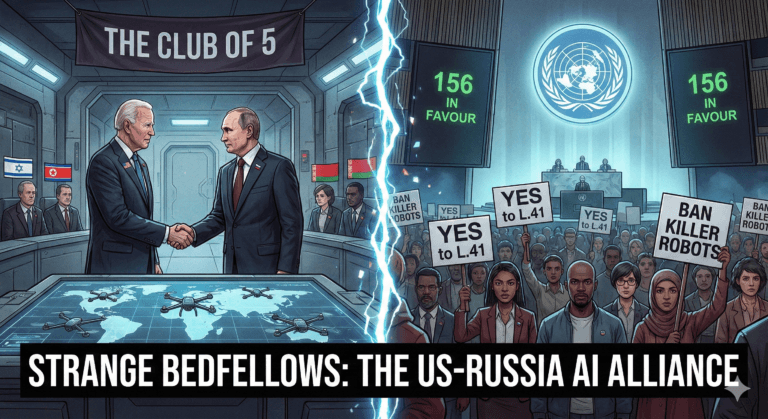

The gridlock at the UN CCW has historically slowed progress on banning ‘killer robots.’ However, the November 2025 adoption of Resolution L.41—which saw a 156-vote majority—indicates that the international community is ready to bypass traditional veto-heavy forums to secure humanitarian safeguards. For a full breakdown of which nations opposed this move, see my analysis: The 5 Against the World.

AI and the Future of Warfare

Extrapolating from current procurement trends in the Indo-Pacific, the future of conflict will likely be defined by algorithmic agency, including drone swarms and ‘Flash Warfare’ where interactions trigger unintended kinetic escalation. I see a future where AI plays an increasingly significant role in warfare. We might see:

- Swarms of autonomous drones: Imagine thousands of small, coordinated drones working together in battle. The U.S., China, and Russia are all working on drone swarm technology [23].

- AI-powered cyber attacks: Future conflicts might be fought primarily in cyberspace, with AI systems launching and defending against attacks at speeds beyond human capability [24].

- Predictive warfare: AI could be used to predict and preempt conflicts before they even begin, raising questions about the nature of deterrence and the potential for pre-emptive strikes [25].

- Human-machine teaming: Rather than fully autonomous systems, we might see closer integration of AI with human soldiers, enhancing human capabilities on the battlefield [26].

- AI diplomats: AI systems might be used to negotiate ceasefires or peace agreements, analysing vast amounts of data to find mutually acceptable solutions [27].

- Cognitive electronic warfare: AI could be used to manipulate the electromagnetic spectrum in ways that confuse or disable enemy systems [28].

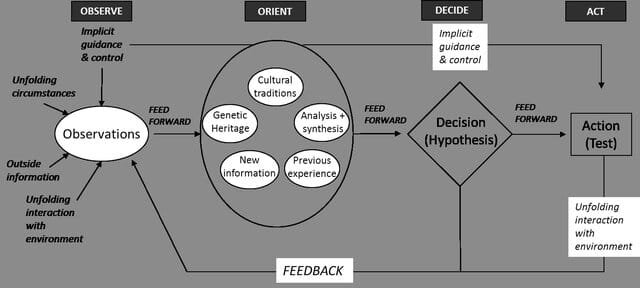

But here’s the kicker – as warfare becomes more AI-driven, the nature of military strategy and diplomacy will change. We might see conflicts resolved in cyberspace before a single shot is fired in the physical world. The integration of AI into command-and-control architectures compresses decision-making timelines, introducing risks of ‘Flash Warfare’ where algorithmic interactions trigger rapid, unintended kinetic escalation..

The speed of AI-driven warfare could also compress decision-making timelines, potentially increasing the risk of escalation. There’s a risk that AI systems could interact in unexpected ways, leading to unintended conflicts or escalations – a kind of “flash war” analogous to the “flash crashes” we’ve seen in financial markets [29].

Moreover, the integration of AI into nuclear command and control systems raises particularly thorny ethical and strategic questions. Could AI increase or decrease the risk of nuclear conflict? The answer remains unclear, but the stakes couldn’t be higher [30].

Balancing Innovation and Ethics

So, how do we move forward without stepping on an ethical landmine? Well, that’s the million-dollar question, isn’t it?

We need robust ethical guidelines for military AI development. This isn’t just a job for the generals and the tech companies; we also need ethicists, policymakers, and civil society involved.

Here are some approaches being considered:

- International treaties: Similar to arms control treaties, we could develop international agreements governing the development and use of military AI. The Campaign to Stop Killer Robots is advocating for such a legally binding instrument [31].

- Ethical guidelines: Many organisations are developing ethical guidelines for AI, including in military contexts. The U.S. Department of Defense, for example, has adopted AI ethics principles [32].

- Human-in-the-loop systems: Ensuring meaningful human control over AI systems, particularly in critical decision-making processes, could help address some ethical concerns [33].

- Transparency and explainability: Developing AI systems that can explain their decision-making processes could help with accountability and trust [34].

- International cooperation: Fostering international dialogue and cooperation on military AI could help prevent an AI arms race and promote responsible development [35].

- Interdisciplinary research: Encouraging collaboration between computer scientists, ethicists, international relations experts, and military strategists to address the multifaceted challenges of military AI [36].

- Public engagement: Promoting public understanding and debate about the implications of military AI to ensure democratic oversight and accountability [37].

International organizations like the UN and NATO have a crucial role to play in shaping the ethics of AI warfare. We need global cooperation to ensure that AI doesn’t become the ultimate weapon of mass destruction.

The IEEE Global Initiative on Ethics of Autonomous and Intelligent Systems is one example of an international effort to develop ethical standards for AI, including in military applications [38]. Similarly, the OECD AI Principles, adopted by 42 countries, provide guidelines for the responsible development of AI, though they are not specifically focused on military applications [39].

AI and the Laws of War

The application of International Humanitarian Law (IHL) to algorithmic systems presents a fundamental challenge to the principle of distinction.

The primary framework governing warfare is International Humanitarian Law (IHL), also known as the Law of Armed Conflict. This includes the Geneva Conventions and their Additional Protocols [40]. These laws were designed with human soldiers in mind, not artificial intelligences. So, how do we adapt?

- Distinction: IHL requires combatants to distinguish between civilian and military targets. Can AI systems make this distinction reliably? Some argue that AI could be more accurate than humans in identifying legitimate targets, while others worry about the complexity of real-world scenarios [41].

- Proportionality: Any attack must be proportional to the military objective. But how do we program an AI to make such nuanced judgments? It’s not just about numbers – it’s about weighing military advantage against potential civilian harm [42].

- Precaution: Combatants must take all feasible precautions to avoid or minimize civilian casualties. Could AI systems be programmed to consistently err on the side of caution? Or would they be pushed to the limits of what’s legally permissible [43]?

- Military Necessity: Actions taken must be necessary to achieve a legitimate military purpose. But can an AI truly understand the broader context of military necessity [44]?

The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) has been grappling with these questions. They’ve emphasized that any new means or methods of warfare, including those using AI, must comply with existing IHL [45]. The primary challenge, however, lies in the algorithmic translation of these legal principles.

Psychological and Social Impacts of AI Warfare

Let’s not forget the human element in all this talk of artificial intelligence. The integration of AI into warfare doesn’t just change the nature of combat – it has profound psychological and social implications.

- Psychological distance: As warfare becomes increasingly automated, there’s a risk of increased psychological distance between combatants and the consequences of their actions. It’s the difference between dropping a bomb in person and pressing a button to launch a drone strike from thousands of miles away [46].

- Post-traumatic stress: Interestingly, drone operators have been found to experience rates of post-traumatic stress similar to traditional combat pilots. What might be the psychological impact on operators working alongside AI systems [47]?

- Public perception: As AI takes on a larger role in warfare, how might this change public perception of war? Could it make warfare seem more sterile or “clean,” potentially lowering the threshold for military interventions [48]?

- Trust in AI systems: How will human soldiers learn to trust (or distrust) AI systems in combat situations? The dynamics of human-machine teaming in high-stress environments is an area ripe for research [49].

- Impact on military culture: The integration of AI could fundamentally change military culture. How might it affect concepts of bravery, sacrifice, and martial virtues [50]?

- Civilian-military divide: As warfare becomes more technologically complex, could it widen the gap between the military and civilian society? This could have implications for democratic oversight of military activities [51].

AI Warfare and Global Stability

Now, let’s zoom out and look at the big picture. How might the integration of AI into warfare affect global stability?

- Deterrence: Traditional concepts of deterrence rely on the threat of retaliation. But how does this work with AI systems? Could the speed and unpredictability of AI-driven warfare undermine strategic stability [52]?

- Arms race dynamics: The AI arms race could lead to rapid escalation and instability. Countries might rush to deploy systems before they’re fully tested or understood, increasing the risk of accidents or unintended escalation [53].

- Power dynamics: AI could potentially level the playing field between larger and smaller military powers. A small country with advanced AI capabilities could punch above its weight, disrupting traditional power balances [54].

- Crisis stability: In a crisis, the pressure to strike first with AI systems (which might be seen as vulnerable to pre-emptive attack) could increase the risk of conflict [55].

- Nuclear stability: The integration of AI into nuclear command and control systems raises particularly worrying questions. Could AI increase or decrease the risk of nuclear conflict [56]?

- Technological dependencies: As militaries become more reliant on AI, they also become more vulnerable to cyber attacks, EMP weapons, or other means of disabling these systems [57].

Economic and Resource Implications

Let’s talk brass tacks – or should I say, gold circuits? The development of military AI has significant economic and resource implications:

- Military spending: The AI arms race is driving increased military spending. Global military expenditure is already at its highest level since the end of the Cold War, and AI is a significant factor in this trend [58].

- Talent pool: The military is now competing with the private sector for AI talent. This “brain drain” could have implications for both sectors and for national competitiveness [59].

- Dual-use technologies: Many AI technologies have both civilian and military applications. This dual-use nature complicates regulation and could lead to tensions between the tech industry and the military [60].

- Economic disruption: As AI reshapes warfare, it could also disrupt defence industries, potentially leading to job losses in some areas and growth in others [61].

- Resource allocation: The focus on military AI could divert resources from other important areas of AI research, such as healthcare or climate change mitigation [62].

The Role of Academia in Military AI Ethics

As a Cambridge student, I can’t help but reflect on the role of academia in all this. Universities are at the forefront of AI research, but how should they engage with military applications of this technology?

- Research ethics: Should universities accept military funding for AI research? This has been a contentious issue, with protests at several institutions [63].

- Dual-use research: Much AI research has potential military applications, even if that’s not the primary intent. How should academics navigate this dual-use dilemma [64]?

- Education and awareness: Universities play a crucial role in educating future AI developers about ethical considerations. How can we ensure that ethics is integrated into technical AI education [65]?

- Interdisciplinary collaboration: Addressing the ethical challenges of military AI requires collaboration between computer scientists, ethicists, international relations experts, and others. Universities are ideal environments for fostering such interdisciplinary work [66].

- Public engagement: Academics can play a vital role in informing public debate about military AI. How can we make these complex issues accessible to a broader audience [67]?

The Way Forward: Recommendations and Future Directions

So, where do we go from here? As we stand at this technological crossroads, what steps can we take to ensure the ethical development and use of AI in warfare and defence? Here are some recommendations to chew on:

International cooperation: We need a global framework for governing military AI. This could take the form of a new international treaty or the expansion of existing agreements [68].

Transparency and accountability: Countries developing military AI should be transparent about their capabilities and intentions. We need mechanisms for international oversight and accountability [69].

Ethical guidelines: Develop and implement robust ethical guidelines for the development and use of military AI. These should be integrated into every stage of the development process [70].

Human control: Maintain meaningful human control over AI systems, especially those with lethal capabilities. This doesn’t mean humans need to control every action, but they should have ultimate decision-making authority [71].

Testing and verification: Develop rigorous testing and verification processes for military AI systems to ensure they behave as intended and comply with ethical guidelines and international law [72].

Interdisciplinary approach: Foster collaboration between technologists, ethicists, policymakers, and military strategists to address the multifaceted challenges of military AI [73].

Public engagement: Promote public understanding and debate about military AI. Democratic oversight requires an informed citizenry [74].

Investment in AI safety: Increase research into AI safety and robustness to reduce the risks of accidents or unintended consequences in military AI systems [75].

Arms control measures: Explore the possibility of arms control agreements specific to AI weapons, similar to existing treaties on chemical and biological weapons [76].

Ethics education: Integrate ethics education into AI and computer science curricula to ensure future developers are equipped to grapple with these complex issues [77].

Conclusion

The transition to AI-integrated warfare demands a shift from reactive ethics to proactive, binding international governance.

The ethical implications of AI in warfare and defence are vast and varied, touching on everything from the nature of combat to the future of international relations. We’ve seen how AI could enhance military decision-making and potentially reduce casualties, but also how it raises profound questions about accountability, the risk of arms races, and the very nature of human control over warfare.

The debate over Lethal Autonomous Weapon Systems remains as contentious as ever, with valid arguments on both sides. As we peer into the future, we see a landscape where AI could fundamentally transform warfare, from swarms of autonomous drones to AI-driven cyber attacks, from predictive warfare to AI diplomats negotiating peace.

We’ve grappled with how AI intersects with the laws of war, its psychological and social impacts, its effects on global stability, and its economic implications. We’ve considered the crucial role that academia must play in navigating these choppy ethical waters.

Balancing innovation and ethics in this field is no easy task. It requires cooperation between nations, dialogue between diverse stakeholders, and a commitment to developing and adhering to robust ethical guidelines. The recommendations we’ve discussed – from international cooperation to maintaining human control, from transparency to public engagement – offer a starting point for this crucial work.

We must stay informed and engaged on this topic. After all, the decisions we make today about military AI will shape the conflicts of tomorrow, and perhaps the very future of humanity. So, dear reader, I encourage you to dig deeper, ask questions, and maybe even join us for a debate.

The ethical implications of AI in warfare and defence are not just academic exercises – they have real-world consequences that could affect us all. As we continue to develop and deploy these technologies, we must remain vigilant, critically examining their impact and striving to ensure they are used in ways that align with our fundamental values and respect for human life and dignity.

In the words of the great British computer scientist Alan Turing,

“We can only see a short distance ahead, but we can see plenty there that needs to be done.”

In the realm of military AI, there’s certainly plenty to be done, and the ethical challenges we face are as complex as they are crucial. But with careful thought, robust debate, and international cooperation, we can work towards harnessing the power of AI in warfare and defence while upholding our ethical principles.

As military architectures increasingly rely on distributed algorithmic agency, the ‘beta-test’ era of military AI must end. Policy must move beyond voluntary codes toward binding international instruments that ensure meaningful human control remains the bedrock of modern warfare. The decisions made at the UN and within academic circles today will define the strategic stability of the next decade. Excellence in technical development must now be matched by excellence in ethical governance.

References

[1] Markets and Markets. (2021). “Artificial Intelligence in Military Market – Global Forecast to 2026.” Link

[2] Valley, G. (1985). “How the SAGE Development Began.” Annals of the History of Computing, 7(3), 196-226. Link

[3] China State Council. (2017). “New Generation Artificial Intelligence Development Plan.” Link

[4] U.S. Army. (2020). “Aided Threat Recognition from Mobile Cooperative and Autonomous Sensors (ATR-MCAS).” Link

[5] Katz, Y., & Bohbot, A. (2017). The Weapon Wizards: How Israel Became a High-Tech Military Superpower. St. Martin’s Press. Link

[6] National Cyber Security Centre. (2019). “AI in Cyber Security.” Link

[7] U.S. Army. (2021). “Integrated Visual Augmentation System (IVAS).” Link

[8] Royal Air Force. (2019). “RAF Launches ‘Project Indira’ to Develop AI-Enabled Maintenance.” Link

[9] U.S. Army. (2021). “Synthetic Training Environment (STE).” Link

[10] United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs. (2021). “Background on LAWS in the CCW.” Link

[11] Horowitz, M. C., & Scharre, P. (2015). “Meaningful Human Control in Weapon Systems: A Primer.” Center for a New American Security. Link

[12] Altmann, J., & Sauer, F. (2017). “Autonomous Weapon Systems and Strategic Stability.” Survival, 59(5), 117-142. Link

[13] UNIDIR. (2018). “The Weaponization of Increasingly Autonomous Technologies: Artificial Intelligence.” Link

[14] Brundage, M., et al. (2018). “The Malicious Use of Artificial Intelligence: Forecasting, Prevention, and Mitigation.” Link

[15] Lin, P. (2010). “Ethical Blowback from Emerging Technologies.” Journal of Military Ethics, 9(4), 313-331. Link

[16] Horowitz, M. C. (2019). “When Speed Kills: Lethal Autonomous Weapon Systems, Deterrence and Stability.” Journal of Strategic Studies, 42(6), 764-788. Link

[17] Roff, H. M., & Moyes, R. (2016). “Meaningful Human Control, Artificial Intelligence and Autonomous Weapons.” Briefing Paper for Delegates at the CCW Meeting of Experts on LAWS. Link

[18] Arkin, R. C. (2009). Governing Lethal Behavior in Autonomous Robots. Chapman and Hall/CRC. Link

[19] Campaign to Stop Killer Robots. (2021). “The Problem.” Link

[20] United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs. (2021). “Background on LAWS in the CCW.” Link

[21] Shane, S., & Wakabayashi, D. (2018). “‘The Business of War’: Google Employees Protest Work for the Pentagon.” The New York Times. Link

[22] Novet, J. (2019). “Microsoft Workers Call for Canceling Military Contract for Technology That Could Turn Warfare into a ‘Video Game’.” CNBC. Link

[23] Hambling, D. (2021). “The Next Generation of Drone Swarms.” IEEE Spectrum. Link

[24] Polyakov, A. (2019). “AI in Cybersecurity: A New Tool for Hackers?” Forbes. Link

[25] Geist, E., & Lohn, A. J. (2018). “How Might Artificial Intelligence Affect the Risk of Nuclear War?” RAND Corporation. Link

[26] Scharre, P. (2018). Army of None: Autonomous Weapons and the Future of War. W. W. Norton & Company. Link

[27] Rossi, F. (2019). “Artificial Intelligence: Potential Benefits and Ethical Considerations.” European Parliament Briefing. Link

[28] Kania, E. B. (2017). “Battlefield Singularity: Artificial Intelligence, Military Revolution, and China’s Future Military Power.” Center for a New American Security. Link

[29] Johnson, J. S. (2020). “Artificial Intelligence: A Threat to Strategic Stability.” Strategic Studies Quarterly, 14(1), 16-39. Link

[30] Boulanin, V., et al. (2020). “Artificial Intelligence, Strategic Stability and Nuclear Risk.” Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. Link

[31] Campaign to Stop Killer Robots. (2021). “The Solution.” Link

[32] U.S. Department of Defense. (2020). “DOD Adopts Ethical Principles for Artificial Intelligence.” Link

[33] Horowitz, M. C., & Scharre, P. (2015). “Meaningful Human Control in Weapon Systems: A Primer.” Center for a New American Security. Link

[34] Gunning, D., & Aha, D. W. (2019). “DARPA’s Explainable Artificial Intelligence Program.” AI Magazine, 40(2), 44-58. Link

[35] United Nations. (2018). “Emerging Technologies and International Security.” Link

[36] Cummings, M. L. (2017). “Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Warfare.” Chatham House. Link

[37] Asaro, P. (2012). “On Banning Autonomous Weapon Systems: Human Rights, Automation, and the Dehumanization of Lethal Decision-making.” International Review of the Red Cross, 94(886), 687-709. Link

[38] IEEE. (2019). “Ethically Aligned Design: A Vision for Prioritizing Human Well-being with Autonomous and Intelligent Systems.” Link

[39] OECD. (2019). “Recommendation of the Council on Artificial Intelligence.” Link

[40] International Committee of the Red Cross. (2015). “International Humanitarian Law and the Challenges of Contemporary Armed Conflicts.” 32nd International Conference of the Red Cross and Red Crescent. Link

[41] Sharkey, N. (2018). “Autonomous Weapons Systems, Killer Robots and Human Dignity.” Ethics and Information Technology, 21(2), 75-87. Link

[42] Schmitt, M. N. (2013). “Autonomous Weapon Systems and International Humanitarian Law: A Reply to the Critics.” Harvard National Security Journal Features. Link

[43] Asaro, P. (2012). “On Banning Autonomous Weapon Systems: Human Rights, Automation, and the Dehumanization of Lethal Decision-making.” International Review of the Red Cross, 94(886), 687-709. Link

[44] Ohlin, J. D. (2016). “The Combatant’s Stance: Autonomous Weapons on the Battlefield.” International Law Studies, 92, 1-30. Link

[45] International Committee of the Red Cross. (2019). “Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Armed Conflict: A Human-Centred Approach.” Link

[46] Royakkers, L., & van Est, R. (2010). “The Cubicle Warrior: The Marionette of Digitalized Warfare.” Ethics and Information Technology, 12(3), 289-296. Link

[47] Chappelle, W., et al. (2019). “Psychological Health Screening of Remotely Piloted Aircraft Operators and Supporting Units.” U.S. Air Force School of Aerospace Medicine. Link

[48] Horowitz, M. C. (2016). “Public Opinion and the Politics of the Killer Robots Debate.” Research & Politics, 3(1). Link

[49] Endsley, M. R. (2017). “From Here to Autonomy: Lessons Learned from Human–Automation Research.” Human Factors, 59(1), 5-27. Link

[50] Coker, C. (2013). “Warrior Geeks: How 21st Century Technology is Changing the Way We Fight and Think About War.” Oxford University Press. Link

[51] Scheipers, S., & Sicurelli, D. (2018). “Guns and Butter? Military Expenditure and Health Spending on the Eve of the Arab Spring.” Defence and Peace Economics, 29(6), 676-691. Link

[52] Geist, E., & Lohn, A. J. (2018). “How Might Artificial Intelligence Affect the Risk of Nuclear War?” RAND Corporation. Link

[53] Johnson, J. S. (2020). “Artificial Intelligence: A Threat to Strategic Stability.” Strategic Studies Quarterly, 14(1), 16-39. Link

[54] Horowitz, M. C. (2018). “Artificial Intelligence, International Competition, and the Balance of Power.” Texas National Security Review, 1(3). Link

[55] Altmann, J., & Sauer, F. (2017). “Autonomous Weapon Systems and Strategic Stability.” Survival, 59(5), 117-142. Link

[56] Boulanin, V., et al. (2020). “Artificial Intelligence, Strategic Stability and Nuclear Risk.” Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. Link

[57] Lewis, D. A. (2022). “On ‘Responsible AI’ in War.” In S. Voeneky, P. Kellmeyer, O. Mueller, & W. Burgard (Eds.), The Cambridge Handbook of Responsible Artificial Intelligence (pp. 488-506). Cambridge University Press. Link

[58] Ding, J., & Dafoe, A. (2023). “Engines of power: Electricity, AI, and general-purpose, military transformations.” European Journal of International Security, 8(3), 377-394. Link

[59] Metz, C. (2018). “Tech Giants Are Paying Huge Salaries for Scarce A.I. Talent.” The New York Times. Link

[60] Brundage, M., et al. (2018). “The Malicious Use of Artificial Intelligence: Forecasting, Prevention, and Mitigation.” Future of Humanity Institute. Link

[61] Hagel, C. (2014). “Defense Innovation Initiative.” U.S. Department of Defense Memorandum. Link

[62] Russell, S., et al. (2015). “Research Priorities for Robust and Beneficial Artificial Intelligence.” Future of Life Institute. Link

[63] Vought, R. T. (2019). “Guidance for Regulation of Artificial Intelligence Applications.” Executive Office of the President, Office of Management and Budget. Link

[64] Brundage, M., Avin, S., Clark, J., Toner, H., Eckersley, P., Garfinkel, B., … & Amodei, D. (2018). “The Malicious Use of Artificial Intelligence: Forecasting, Prevention, and Mitigation.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1802.07228. Link

[65] Boddington, P. (2017). “Towards a Code of Ethics for Artificial Intelligence.” Springer. Link

[66] Floridi, L., & Cowls, J. (2019). “A Unified Framework of Five Principles for AI in Society.” Harvard Data Science Review, 1(1). Link

[67] Bryson, J. J., & Winfield, A. F. (2017). “Standardizing Ethical Design for Artificial Intelligence and Autonomous Systems.” Computer, 50(5), 116-119. Link

[68] Scharre, P. (2018). “Army of None: Autonomous Weapons and the Future of War.” W. W. Norton & Company. Link

[69] Crootof, R. (2015). “The Killer Robots Are Here: Legal and Policy Implications.” Cardozo Law Review, 36(5), 1837-1915. Link

[70] Cath, C., Wachter, S., Mittelstadt, B., Taddeo, M., & Floridi, L. (2018). “Artificial Intelligence and the ‘Good Society’: The US, EU, and UK Approach.” Science and Engineering Ethics, 24(2), 505-528. Link

[71] Roff, H. M. (2019). “The Frame Problem: The AI ‘Arms Race’ Isn’t One.” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 75(3), 95-98. Link

[72] Yampolskiy, R. V. (2016). “Artificial Intelligence Safety Engineering: Why Machine Ethics Is a Wrong Approach.” In Philosophy and Theory of Artificial Intelligence 2015 (pp. 389-396). Springer. Link

[73] Taddeo, M., & Floridi, L. (2018). “How AI Can Be a Force for Good.” Science, 361(6404), 751-752. Link

[74] Cave, S., & ÓhÉigeartaigh, S. S. (2018). “Bridging the Gap: The Case for an AI Safety Research Program.” AI & Society, 33(4), 465-476. Link

[75] Amodei, D., Olah, C., Steinhardt, J., Christiano, P., Schulman, J., & Mané, D. (2016). “Concrete Problems in AI Safety.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1606.06565. Link

[76] Asaro, P. M. (2012). “On Banning Autonomous Weapon Systems: Human Rights, Automation, and the Dehumanization of Lethal Decision-Making.” International Review of the Red Cross, 94(886), 687-709. Link

[77] Boddington, P. (2017). “Towards a Code of Ethics for Artificial Intelligence.” Springer. Link

Avi is a researcher educated at the University of Cambridge, specialising in the intersection of AI Ethics and International Law. Recognised by the United Nations for his work on autonomous systems, he translates technical complexity into actionable global policy. His research provides a strategic bridge between machine learning architecture and international governance.

3 Comments