The Myth of the “Third World”: Why We Must Abandon the Language of Empire

1. Introduction: The Violence of Nomenclature

The act of naming is never a neutral linguistic exercise; it is an exercise in power. To categorise a nation, a people, or a civilisation is to impose a specific epistemological framework upon them, often one that serves the interests of the classifier rather than the classified. In the discourse of international relations and global economics, few taxonomies have proven as persistent, as misleading, and as ideologically charged as the bipartite division of the globe into “First” and “Third” worlds, or their sanitised successors, “Developed” and “Developing” nations. These terms, while ubiquitous in media, policy, and colloquial conversation, function not as accurate descriptors of empirical reality, but as relics of a specific historical moment—the Cold War—and a specific ideological project—Eurocentric imperialism.

This report posits that the continued usage of these dichotomous labels constitutes a form of “epistemic violence.” They are empirically baseless in the twenty-first century, obscuring the complex economic stratification defined by the “Four Level” framework proposed by Hans Rosling and the Gapminder Foundation.[1] Furthermore, they are rooted in a racist, teleological worldview that centres Western whiteness as the ultimate destination of human history, relegating the “Global South” (or “Global Majority”) to a perpetual state of “becoming” or inferiority.[2]

The implications of this broken lexicon extend far beyond semantics. As the analysis will demonstrate, these terms distort foreign policy, justify neo-colonial interventionism, and hinder the recognition of the severe “mal-development”—ecological and social—plaguing the so-called “First World”.[3] By deconstructing the genealogy of these terms, from Alfred Sauvy’s original coinage in 1952 to the World Bank’s current income thresholds, this report argues for an immediate and rigorous semantic decolonisation. We must abandon the binary map of the world in favour of a nuanced, data-driven, and dignified vocabulary that reflects the multipolar reality of the modern era.

2. The Archaeology of a Broken Lexicon: Origins and Semantic Drift

To dismantle the “First/Third World” hierarchy, one must first excavate its origins. Contrary to contemporary usage, which associates the “Third World” exclusively with poverty and dysfunction, the term was born out of a revolutionary political aspiration.

2.1 Alfred Sauvy and the Revolutionary Metaphor

The term Tiers Monde (Third World) was coined on August 14, 1952, by the French demographer and economic historian Alfred Sauvy in an article for L’Observateur titled “Trois mondes, une planète” (Three Worlds, One Planet).[4] Sauvy was analyzing the geopolitical stagnation of the early Cold War, where the globe appeared locked in a binary struggle between the capitalist West (the First World) and the communist East (the Second World).

Sauvy’s brilliance lay in his refusal to accept this duality. He drew a deliberate historical parallel to the French Revolution of 1789. In pre-revolutionary France, society was divided into three estates: the First Estate (the clergy), the Second Estate (the nobility), and the Third Estate (the commoners). The Third Estate, though disenfranchised and despised, represented the vast majority of the population and the true vital force of the nation. Sauvy famously concluded his article by writing: “The Third World has, like the Third Estate, been ignored, exploited, and despised, and it too wants to be something”.[4]

In this genesis, “Third World” was not a label of pity; it was a label of agency. It referred to the nations of Africa, Asia, and Latin America—many barely emerging from the yoke of colonialism—who refused to align themselves with either the NATO bloc (United States) or the Warsaw Pact (Soviet Union). It was the terminology of the Non-Aligned Movement, formalised at the Bandung Conference of 1955. Leaders like Nehru of India, Sukarno of Indonesia, and Nasser of Egypt embraced the concept as a declaration of independence from the superpower rivalry.

2.2 The Erasure of the Second World and the “Development” Shift

However, language is fluid, and the political radicalism of the term was quickly neutralised by the West. Throughout the 1960s and 70s, as the Cold War ossified, the “Second World” (the Soviet bloc) became a closed system, isolated from the global capitalist economy. The “First World”—comprising the US, Western Europe, Japan, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand—began to define itself not just by its political alliance, but by its economic prosperity and industrial capitalism.[4]

Simultaneously, the “Third World” was stripped of its political definition (non-alignment) and redefined by its economic struggle. It became synonymous with “underdevelopment,” poverty, famine, and instability. The “First World” became the Saviour; the “Third World” became the Victim. This semantic drift was convenient for Western powers; it allowed them to frame their interventions in the Global South not as imperialist manoeuvring for Cold War influence, but as benevolent “aid” and “development”.[5]

The ‘First World’ became the Saviour; the ‘Third World’ became the Victim.

The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 delivered the final blow to the original taxonomy. With the “Second World” effectively vanishing as a geopolitical entity, the “First” and “Third” numbering system lost its logical sequence. Yet, it survived as a zombie category. Without the “Second” to mediate, the “Third World” became a floating signifier for everything the West feared or despised: chaos, disease, overpopulation, and non-whiteness. It became a racial category masquerading as an economic one.[4]

2.3 The “Developing” Trap: A Teleological Fallacy

Recognising the crudeness of the numerical system, international institutions such as the United Nations and the World Bank increasingly pivoted to the dichotomy of “Developing” vs. “Developed” in the late 20th century. While superficially more polite, this terminology is intellectually more insidious because it imposes a teleological view of history.

Teleology acts on the premise that history has a single direction and a specific endpoint. The term “Developed” (a past participle) implies a finished state. It suggests that nations like the United States or the United Kingdom have reached the pinnacle of human societal evolution. It implies there is no further room for structural improvement, only maintenance.[3] This is a profound arrogance that ignores the deep social fractures, inequalities, and ecological unsustainability inherent in Western industrial societies.

Conversely, “Developing” (a present participle) implies a linear journey. It presumes that the destiny of a country like Nigeria or Vietnam is to essentially become the United States. It suggests that there is only one valid model of society—consumerist, industrial, liberal democracy—and that all other societies are merely in a transitional phase toward that model.[2] This perspective is rooted in “Modernisation Theory,” popularised by economists like Walt Rostow in the 1960s, which posited that all societies must pass through identical “stages of growth” to achieve “civilisation.”

This framework denies the possibility that non-Western nations might forge alternative paths to prosperity that prioritize different values—such as community cohesion, spiritual well-being (e.g., Bhutan’s Gross National Happiness), or ecological balance—over raw GDP accumulation. By labelling them “developing,” we conceptually trap them in a game where the West sets the rules and the finish line, ensuring the “Third World” can never truly win.[6]

3. The Colonial Matrix of Power: Race, Whiteness, and Hierarchy

To understand the tenacity of these terms, one must look beyond economics to the racial stratifications of the modern world system. The “First/Third World” binary is a direct descendant of the colonial distinction between “Civilised” and “Savage,” filtered through the sanitising language of economics.

3.1 The Global Colour Line

At the turn of the twentieth century, the sociologist W.E.B. Du Bois famously prophesied that the problem of the twentieth century would be “the problem of the colour line”—the relation of the darker to the lighter races of men.[7] This colour line was not erased by decolonisation; it was merely remapped onto the “Development” hierarchy.

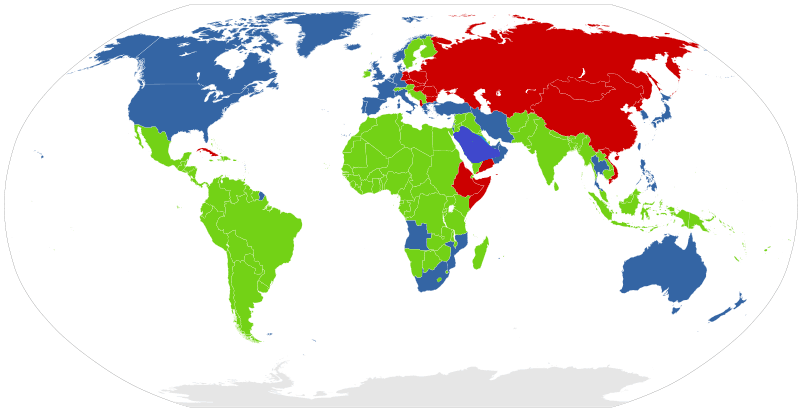

The “First World” is overwhelmingly associated with whiteness. Its core members—North America, Western Europe, Australia—are the historic beneficiaries of colonialism and the transatlantic slave trade. The “Third World” is almost exclusively comprised of Black, Brown, and Asian populations.[8] Critical race scholars argue that “development” discourse functions as a mechanism to maintain white supremacy without explicitly using racial language. When a commentator dismisses a nation as “Third World,” they are often invoking a stereotype of incompetence, corruption, and backwardness that historically justified colonial rule.[9]

Scholars like Anibal Quijano and Walter Mignolo describe this as the “Coloniality of Power.” They argue that while formal colonialism (the planting of flags and administration by viceroys) may have ended, the power structures (economic dependency, cultural hierarchy, racial knowledge systems) remain intact.[2] The “Developed/Developing” dichotomy is the linguistic enforcement of this coloniality. It frames the white West as the standard of universal humanity and the non-white South as the “Other” that must be managed, studied, and reformed.[2]

3.2 Internal Colonialism: The Third World Within

The geographic rigidity of the “First” and “Third” world distinction also serves to erase the existence of racialized poverty within wealthy nations. Sociologists in the 1960s and 70s, such as Pablo González Casanova and Rodolfo Stavenhagen, developed the theory of “internal colonialism” to describe the relationship between dominant elites and marginalised minorities within a single state.[10]

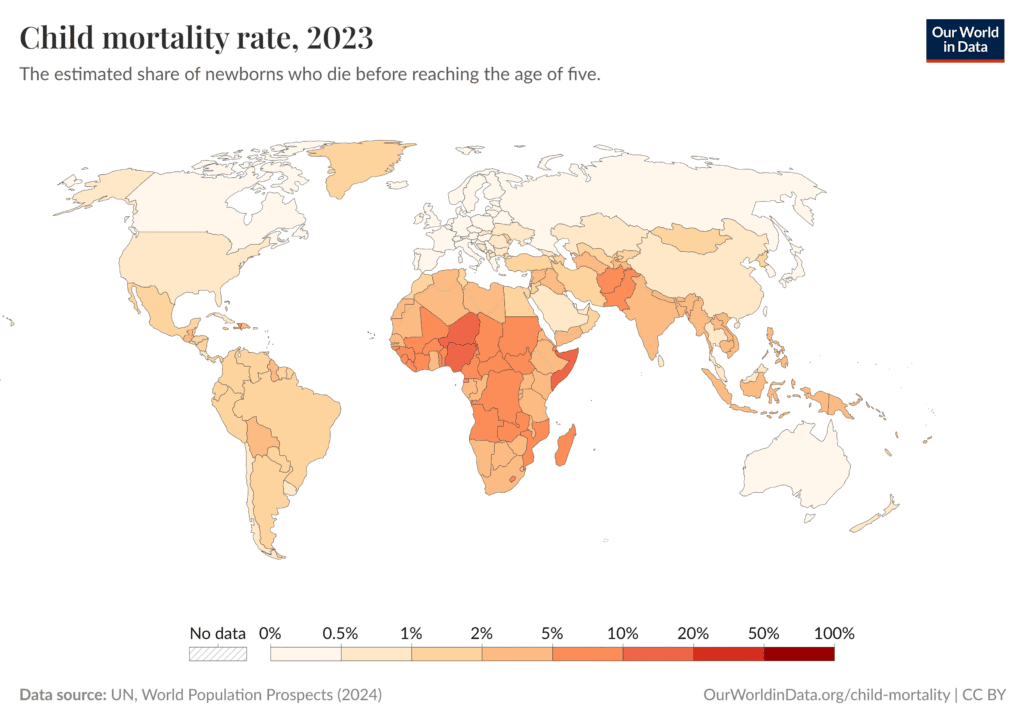

By insisting that the United States is a “First World” country, we render invisible the conditions in places like the Mississippi Delta, the Pine Ridge Reservation, or the crumbling inner cities of the Rust Belt. In these internal colonies, life expectancy, infant mortality, and access to clean water often mirror the statistics of the so-called “Third World”.[11] For example, the water crisis in Flint, Michigan, or the lack of sanitation in parts of the rural American South, are “Third World” conditions masked by the national aggregate wealth.

Similarly, the concept erases the “First World” elites living within the “Third World.” In cities like Mumbai, Sao Paulo, or Nairobi, there are populations living in gated communities with access to world-class healthcare, international education, and luxury consumption that rivals or exceeds that of the average European. The binary terminology blinds us to class solidarity across borders, encouraging us to think in terms of national blocs rather than global stratifications of capital and labour.[5]

3.3 The White Saviour Industrial Complex

The language of “developing” nations creates a psychological dynamic of charity rather than justice. It facilitates the “White Saviour Industrial Complex,” a term popularised by Teju Cole, where the West perceives itself as the benevolent donor of civilisation to a needy, passive South.[3]

This is evident in the visual culture of development aid: the ubiquitous imagery of white aid workers holding Black children, or Western engineers pointing at blueprints while locals look on passively. This imagery reinforces the hierarchy of the “active” First World and the “passive” Third World.[9] It obscures the reality that the global financial system—structured by “First World” institutions like the IMF and WTO—often extracts more wealth from the Global South in debt repayments, resource extraction, and illicit financial flows than it ever returns in aid.[3] The terminology of “aid” and “development” masks this extractive reality, presenting the West as a generous benefactor rather than a beneficiary of historical and ongoing plunder.

4. The Empiricism of Error: Why the Binary Fails the Data

Even if one were to set aside the historical and ethical objections, the “Developed/Developing” taxonomy is scientifically bankrupt. It simply no longer fits the data. The world has changed fundamentally since 1952, yet our language has remained frozen in amber.

4.1 The Myth of the “Gap”

The late Hans Rosling, a physician and statistician who founded the Gapminder Foundation, dedicated his life to fighting what he called the “Gap Instinct”—the human tendency to divide all things into two distinct, often conflicting groups, with an imagined gap between them.[1]

In 1965, the world did resemble a binary system. If one plotted countries by life expectancy and income, there were two distinct clusters: a “First World” box (high income, long lives, small families) and a “Third World” box (low income, short lives, large families). The “gap” between them was real and profound.

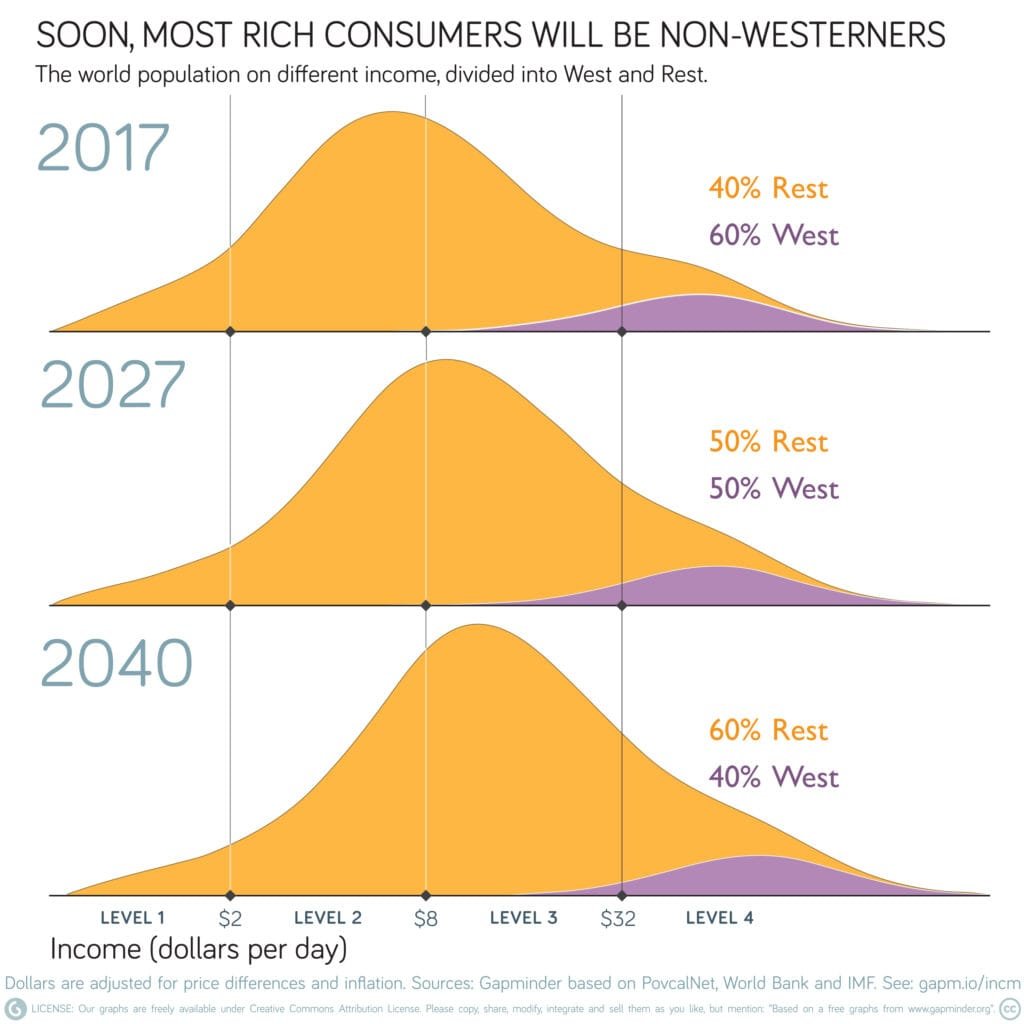

However, Rosling’s data visualisation demonstrates that by 2017, this gap had completely vanished. The “camel” (two humps) has become a “dromedary” (one hump). The vast majority of the world’s population—roughly 75%—lives in middle-income countries.[1]

Countries like Brazil, Turkey, Mexico, Thailand, China, and Indonesia have achieved life expectancies and health outcomes that rival the West, despite having lower per capita incomes.

To continue calling these nations “developing” alongside fragile states like Somalia or Afghanistan is analytically useless. It lumps together economies with advanced industrial bases and global supply chain integration with subsistence agrarian economies. This lack of nuance leads to catastrophic errors in policy and investment.[12]

4.2 The Four Levels of Income: A High-Resolution Framework

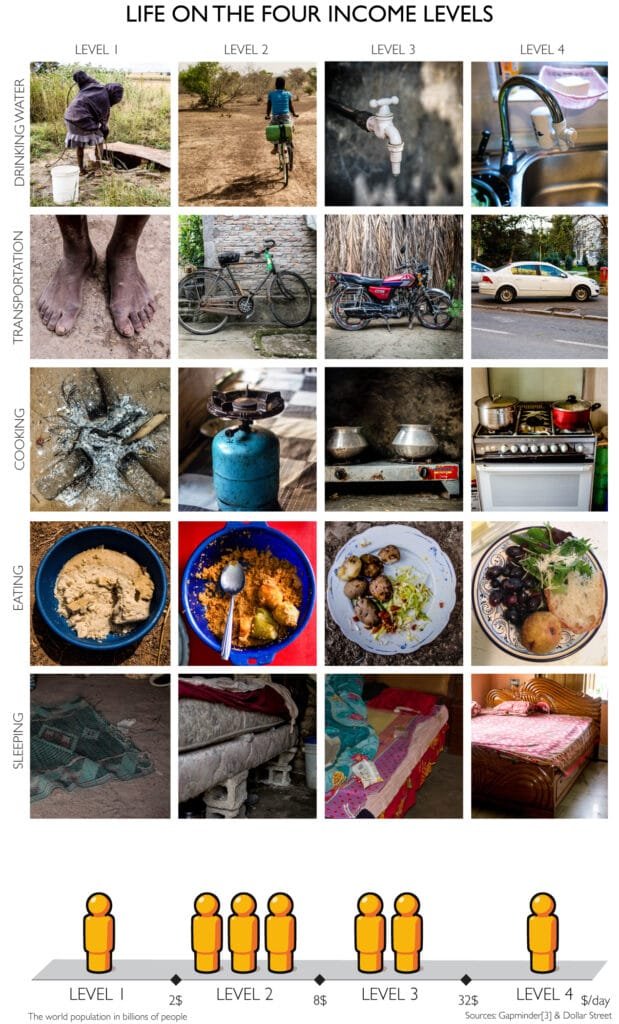

To replace the low-resolution binary, Rosling proposed a four-level framework based on daily income, adjusted for purchasing power parity (PPP). This model provides a far more accurate picture of human life in the 21st century[1]:

| Level | Daily Income ($) | Pop. (Approx) | Characteristics of Life | Typical Transportation | Water Source |

| Level 1 | < $2 | ~1 Billion | Extreme Poverty. Struggle for food daily. Cooking over open fire. No shoes. High child mortality. | Walking (barefoot) | Walking to a dirty mud hole/distant well. |

| Level 2 | $2 – $8 | ~3 Billion | Lower-Middle. Can afford shoes, perhaps a bicycle. Kids go to school but may drop out. Gas stove. | Bicycle / Bus | Community tap / borehole (cold). |

| Level 3 | $8 – $32 | ~2 Billion | Upper-Middle. Cold water tap in-house. Electricity. Fridge. Motorbike. High school/Uni. | Motorbike / Scooter | Tap in house (cold). |

| Level 4 | > $32 | ~1 Billion | High Income. Hot and cold water. Car. Air travel. Eating out. Complete education. | Private Car / High-speed train | Hot & Cold tap in house. |

Analytical Insight: The “Developing World” label typically encompasses Levels 1, 2, and 3. This is an absurdity. The leap from Level 1 to Level 2 is the most significant in human history—it is the escape from extreme poverty. The leap from Level 2 to Level 3 brings industrialisation and electricity. A person at Level 3 (e.g., a factory manager in Vietnam) has more in common with a person at Level 4 (a retail worker in Spain) than they do with a subsistence farmer at Level 1.[1]

A person at Level 3 (e.g., a factory manager in Vietnam) has more in common with a person at Level 4 (a retail worker in Spain) than they do with a subsistence farmer at Level 1.

By collapsing Levels 1-3 into a single “Third World” bucket, we fail to see the progress of the 3 billion people at Level 2 and the 2 billion at Level 3. We miss the rise of the global middle class, which is the most significant economic story of our time.

4.3 The Convergence of Social Indicators

The persistence of the “Third World” stereotype relies on outdated data regarding health and population.

- Infant Mortality: In 1950, “developing” countries had infant mortality rates often exceeding 200 per 1,000 births. Today, countries like Malaysia (Level 3/4) have rates lower than some regions of the United States. The global average has plummeted, converging toward the Western standard.[13]

- Fertility Rates: The Malthusian fear of a “Third World population bomb” is factually incorrect. The majority of countries in Asia and Latin America have reached replacement-level fertility (approximately 2.1 children per woman) or lower. The large family size is now a phenomenon restricted largely to Level 1 countries, primarily in Sub-Saharan Africa, and even there, rates are falling as education rises.[14]

When we use terms like “developing,” we are summoning a mental image of the world from fifty years ago. We are failing to be “smart enough” to recognise the reality of the present.[12]

5. Institutional Inertia: The World Bank and the Politics of Classification

If the terms are so flawed, why do they persist in the corridors of power? The answer lies in the bureaucratic machinery of international institutions such as the World Bank, the IMF, and the WTO.

5.1 The Arbitrariness of the Thresholds

The World Bank classifies economies into four income groups: Low, Lower-Middle, Upper-Middle, and High. These classifications are updated annually every July 1st, based on GNI (Gross National Income) per capita.[15]

For the 2024 fiscal year, the thresholds are [15]:

- Low Income: < $1,135

- Lower-Middle Income: $1,136 – $4,495

- Upper-Middle Income: $4,496 – $13,935

- High Income: > $13,935

While this is more granular than “Developed/Developing,” it is still fundamentally arbitrary. A country with a GNI per capita of $13,930 is considered “Middle Income” (often grouped with “Developing”), while a country with $13,940 is “High Income” (Developed). Does the quality of life, institutional stability, or human rights record change magically at that $10 increment?

Furthermore, these thresholds are absolute numbers that do not account for purchasing power or inequality. A country like Equatorial Guinea has at times been classified as “High Income” or “Upper Middle Income” due to oil revenue, yet the vast majority of its population lives in Level 1 poverty. The aggregate number hides the distribution, allowing the “developed” label to mask deep suffering, or the “developing” label to mask pockets of immense wealth.[13]

5.2 The “Smart Enough” Algorithm and Political Gaming

Hans Rosling recounted an interaction with the World Bank where he criticised their binary classification. He was told that their algorithm was “smart enough” to know where to draw the line. Rosling argued that “it matters very little where we draw the line… this kind of hairsplitting is not particularly meaningful”.[12]

The hairsplitting, however, is deeply political. In the World Trade Organisation (WTO), countries can self-designate as “developing.” This status grants them “Special and Differential Treatment” (SDT), allowing for longer transition periods to implement agreements and protection for their domestic industries.[16] This leads to the anomaly of economic powerhouses like China, South Korea, or Singapore holding onto “developing” status long after they have industrialised, while true Level 1 nations struggle to compete.

Conversely, there is the “Middle Income Trap.” When a country “graduates” from Low to Middle income status based on World Bank thresholds, it often loses access to concessional financing and grants from donors, despite still having weak institutions and high poverty. The classification system thus becomes a trap, punishing success and ignoring vulnerability.[3]

6. The Post-Development Critique: Deconstructing the Discourse

To truly understand why “developing” is a racist and outdated term, we must engage with Post-Development Theory. Thinkers like Arturo Escobar, Gustavo Esteva, and Majid Rahnema argue that “development” is not a benevolent economic process, but rather a geopolitical discourse designed to manage and control the non-Western world.[6]

6.1 Development as Cultural Imperialism

Escobar, in his seminal work Encountering Development [17], argues that the “Third World” was effectively invented by Western discourse after World War II. Before 1945, African and Asian societies were seen as different, perhaps savage, but distinct. After Truman’s Point Four program in 1949, they were suddenly defined by what they lacked (industry, capital, modern technology).

This definition delegitimised all indigenous forms of knowledge and social organisation.

- Agriculture: Traditional permaculture and subsistence farming—sustainable for millennia—were labelled “backward.” “Development” meant replacing them with industrial monocultures, chemical fertilisers, and cash crops for export.[8]

- Community: Complex kinship networks and communal land ownership were seen as obstacles to the “rational” individual, private property, and labour mobility required for capitalism.

By using the term “developing,” we are implicitly validating this destruction. We are saying that the history of the non-West is merely a waiting room for Western modernity. Post-development theorists argue that we should not be seeking “alternative developments” (better ways to develop), but “alternatives to development”—ways of living that reject the hegemony of economic growth and consumerism entirely.[17]

6.2 Epistemic Violence

Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak used the term “epistemic violence” to describe how Western knowledge systems silence the subaltern. When a Western expert arrives in a “developing” country with a pre-packaged solution (the “standard package” of neoliberal reforms), they are committing epistemic violence.[8] They are assuming that the local population has no relevant knowledge to solve their own problems.

The label “Third World” acts as a silencer. It signals that the people living there are objects of study, not subjects of history. It creates a dynamic where the West speaks for the Third World, but never listens to it.[5] This is why the “Third World” has, as Arif Dirlik notes, “penetrated the inner sanctum of the first world”—through migration and diaspora, the silenced voices are now challenging the First World from within, disrupting the neat binary of the classifier.[5]

7. Ecological Realities: The Myth of the “Developed” World

Perhaps the most devastating argument against the “Developed” label is the ecological one. If “Developed” implies a desirable end-state, a model for the rest of the world to emulate, then the “First World” is arguably the least developed model in human history.

7.1 Mal-development and the Ecological Footprint

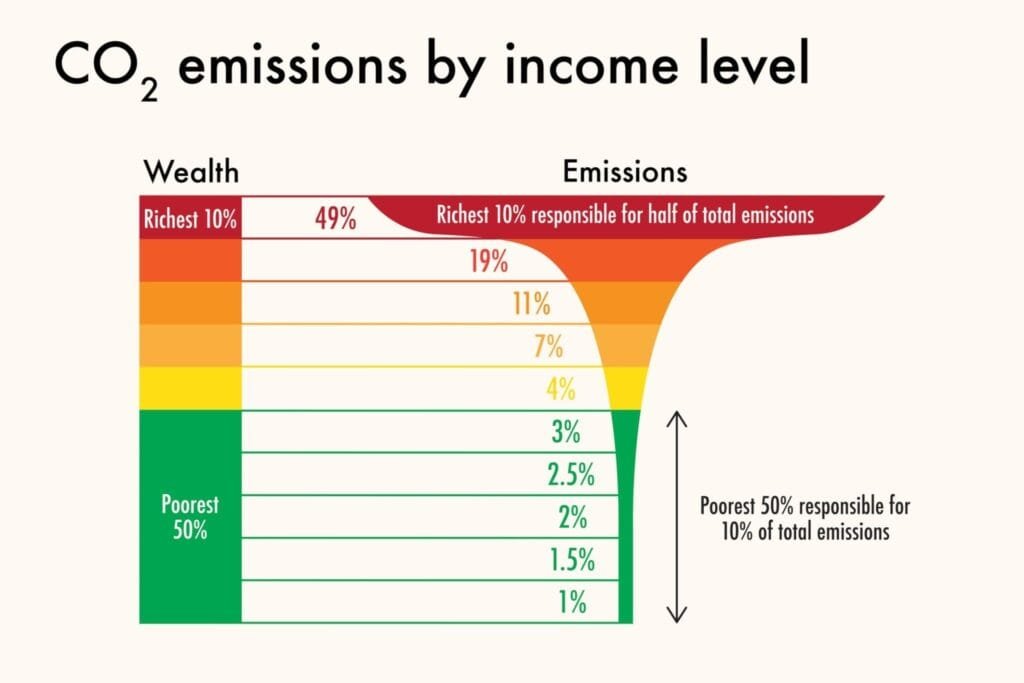

The “First World” lifestyle is built on a profound ecological debt. The United States and Western Europe achieved their “development” by colonising the atmosphere with carbon dioxide and the oceans with plastic.

If every person in the “Third World” consumed resources at the rate of the average American, we would need five planets to sustain us.[18]

From this perspective, the ‘First World’ is not developed; it is mal-developed. It is over-consuming, inefficient, and suicidal.

From this perspective, the “First World” is not developed; it is mal-developed. It is over-consuming, inefficient, and suicidal. To tell a country like Sri Lanka or Costa Rica that they should “develop” into the United States is to invite global collapse.

7.2 Doughnut Economics: A New Standard

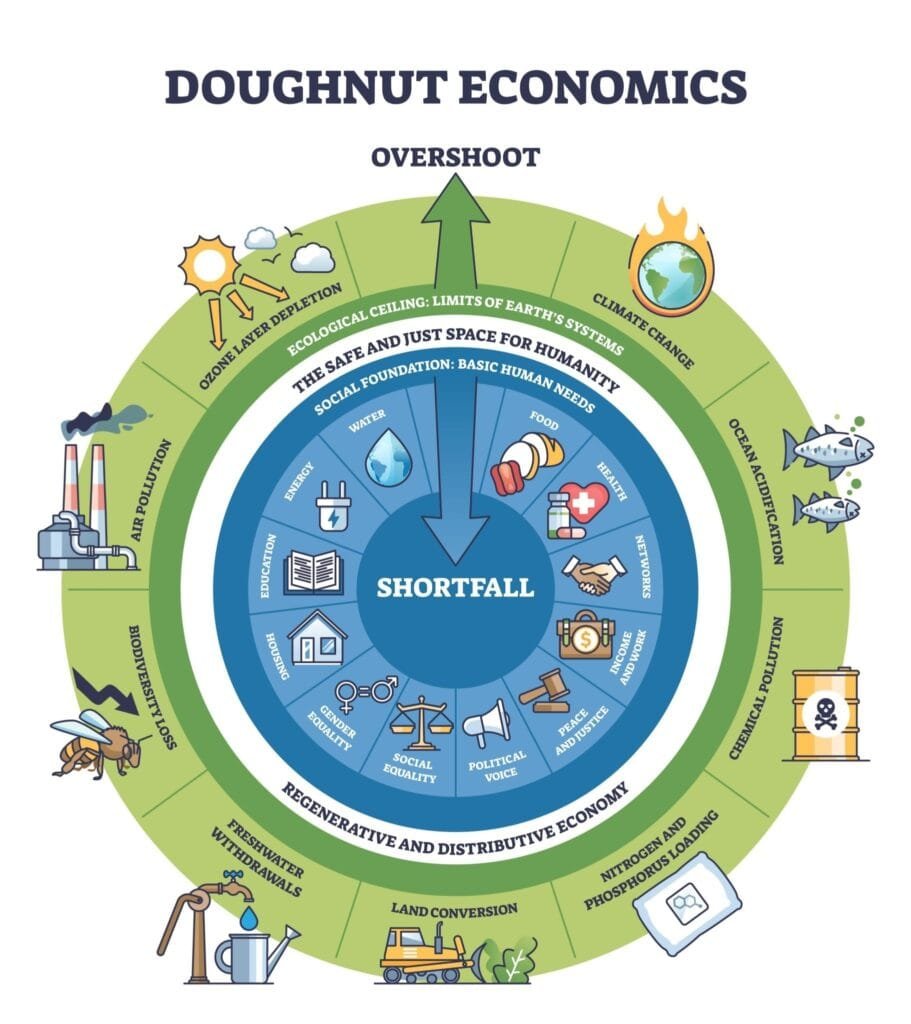

Economist Kate Raworth and researchers like Daniel O’Neill have proposed a new metric for success: the “Doughnut”.[18]

- The Inner Ring: The social foundation (food, water, health, education).

- The Outer Ring: The ecological ceiling (climate change, nitrogen loading, biodiversity loss).

The goal of humanity is to live in the “safe and just space” of the Doughnut—meeting human needs without destroying the planet.

- The Data: When measured this way, no country is developed.

- The “First World” (US, UK, Germany) is failing the ecological ceiling. They are “over-developed.”

- The “Third World” (Malawi, Yemen) is failing the social foundation.

- The countries closest to the ideal are often “Middle Income” nations like Costa Rica or Vietnam, which achieve high life satisfaction and health with relatively low ecological footprints.

By retaining the term “Developed,” we validate an ecologically destructive model. We obscure the urgent need for the West to “de-grow” or “de-develop” its resource consumption. The future of humanity likely lies in learning from the low-carbon, community-centric innovations of the so-called “Third World”—frugal innovation (jugaad), repair culture, and communal resource management—rather than the disposable culture of the “First World”.[18]

8. Toward a New Lexicon: Precision, Dignity, and Factfulness

If the old terms are racist, inaccurate, and ecologically dangerous, what words should we use? The goal is not just “political correctness,” but scientific precision and human dignity.

8.1 The “Global South” and “Global North”

Currently, “Global South” is the preferred term in academia and the UN to replace “Third World”.[2]

- Definition: Broadly refers to the regions of Latin America, Asia, Africa, and Oceania. “Global North” refers to North America, Europe, and developed parts of East Asia.

- Pros: It shifts the focus from economic hierarchy to geopolitical history. It acknowledges the shared legacy of colonialism and the current structural marginalisation in global institutions.

- Cons: It is geographically inaccurate (Australia is “North” economically but South geographically). It still lumps diverse nations together.[3]

- Verdict: Useful for political and sociological contexts to describe power dynamics, but still a blunt instrument for economics.

8.2 The “Majority World”

This term is gaining traction among activists and sociologists.

- Rationale: The “Third World” comprises over 80% of the human population. Calling them “Third” or “Developing” frames them as the outlier or the minority. “Majority World” centres them as the norm of human experience.[3]

- Pros: Rhetorically powerful. It flips the script, forcing the “First World” to see itself as the demographic anomaly (the “Minority World”).

- Verdict: Excellent for challenging Western-centrism in essays and opinion pieces.

8.3 The Rosling Levels (1-4)

For business, economics, and data analysis, the Gapminder Levels are the gold standard.[1]

- Usage: “Markets in Level 2 economies,” “Consumers in Level 3 households.”

- Pros: Removes moral judgment. Focuses on material reality (access to water, electricity, disposable income). Allows for granular targeting.

- Verdict: Essential for investors, policymakers, and technical writers.

8.4 Descriptive Specificity

The most authoritative approach is often to describe exactly what you mean.

- Instead of “Developing Country,” use: “Emerging Market,” “High-Growth Economy,” “Agrarian Economy,” “Post-Colonial State,” or simply the name of the region (“Southeast Asian economies”).

- Instead of “First World,” use: “OECD Nations,” “High-Income Economies,” or “Historic Emitters.”

9. Conclusion: The Power of Language in a Multipolar World

The persistence of the terms “Third World,” “First World,” “Developing,” and “Developed” is a testament to the endurance of colonial thought patterns in our modern institutions. These words are not neutral descriptors; they are loaded weapons that perpetuate a hierarchy of human worth. They obscure the reality of global inequality, justify paternalistic intervention, and hide the rapid progress that has occurred in the majority of the world.

For my audience, rejecting this terminology is an act of intellectual leadership. It signals a refusal to accept lazy stereotypes and a commitment to engaging with the world as it actually is in 2025 and beyond—complex, multipolar, and converging.

We must stop asking when the “Third World” will catch up to the “First.” Instead, we must recognise that we are all on a single, shared planet, facing shared threats like climate change and pandemics, where the old hierarchies offer no protection. The “Developed” world has much to learn from the resilience and innovation of the “Majority World.” The map has changed; it is time our language caught up.

Table: Summary of Terminological Evolution

| Legacy Term | Implications (Why it is wrong) | Better Alternative | Context for Use |

| Third World | Discussing historic centres of capital. | Global South | Political solidarity; discussing post-colonial history. |

| First World | Implies superiority; “White” standard; ignores internal poverty. | Global North / OECD | Discussing historic centers of capital. |

| Developing | Teleological; assumes linear path to Western capitalism; masks diversity. | Emerging Markets / Level 2 & 3 | Economics; Business; Investment analysis. |

| Developed | Implies perfection/completion; ignores ecological unsustainability. | High-Income Economies | World Bank classification (technical). |

| Non-Western | Defines by negation (what they are not). | Majority World | Sociology; Cultural critique; Demographics. |

Key Takeaways for the Reader

- History Matters: “Third World” was originally a term of revolutionary pride (Sauvy, 1952) that was hijacked to mean “poor” by Western powers. Using it today erases that history of resistance.

- Data Over Dogma: The binary “rich/poor” world no longer exists. Most of humanity lives in the middle (Levels 2 and 3). Policy must reflect this continuum, not a binary gap.

- Words are Power: Calling a country “developing” validates a colonial worldview where the West is the parent and the rest of the world is the child. It is a form of “epistemic violence.”

- Ecological Reality: The “First World” is not the goal; it is an ecological warning. True development in the 21st century must look different from the resource-intensive path of the 20th century.

- Be Specific: In authoritative writing, avoid catch-all terms. Use specific economic, geographic, or social descriptors to respect the unique trajectory of each nation.

References

- Rosling, H., Rosling, O., & Rönnlund, A. R. (2018). Factfulness: Ten Reasons We’re Wrong About the World. Sceptre.

- Mignolo, W. D. (2011). The Darker Side of Western Modernity: Global Futures, Decolonial Options. Duke University Press.

- Hickel, J. (2017). The Divide: A Brief Guide to Global Inequality and its Solutions. William Heinemann.

- Sauvy, A. (1952). “Trois mondes, une planète”. L’Observateur, No. 118.

- Dirlik, A. (1994). “The Postcolonial Aura: Third World Criticism in the Age of Global Capitalism”. Critical Inquiry, 20(2).

- Esteva, G. (2010). “Development”. In The Development Dictionary: A Guide to Knowledge as Power. Zed Books.

- Du Bois, W. E. B. (1903). The Souls of Black Folk. A.C. McClurg & Co.

- Said, E. W. (1978). Orientalism. Pantheon Books.

- González Casanova, P. (1965). “Internal Colonialism and National Development”. Studies in Comparative International Development.

- UN Human Rights Office. (2017). Statement on Visit to the USA by Professor Philip Alston.

- The World Bank. (2023). “Mortality rate, infant (per 1,000 live births)”.

- UNFPA. (2022). State of World Population 2022.

- The World Bank. (2024). “World Bank country classifications by income level for 2024-2025”. Data Blog.

- Gapminder Foundation. (2018). “Gapminder Tools: Income Levels”.

- WTO. “Who are the developing countries in the WTO?”.

- Escobar, A. (1995). Encountering Development: The Making and Unmaking of the Third World. Princeton University Press.

- Spivak, G. C. (1988). “Can the Subaltern Speak?”. In Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture. University of Illinois Press.

- Raworth, K. (2017). Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist. Chelsea Green Publishing.

Avi is a researcher educated at the University of Cambridge, specialising in the intersection of AI Ethics and International Law. Recognised by the United Nations for his work on autonomous systems, he translates technical complexity into actionable global policy. His research provides a strategic bridge between machine learning architecture and international governance.