From “Triads” to “Scam States”: The political economy of industrial‑scale cyber fraud, drug production, and forced criminality in mainland Southeast Asia, 2012–2025

Films like Kill Bill and John Wick popularise a romanticised image of Asian organised crime built around codes of honour and tightly knit brotherhoods. Across the Mekong subregion today, especially in Myanmar, Cambodia, and Laos, the reality looks very different. Empty or underutilised casinos and SEZs have been converted into industrial “compounds” that run cyber‑enabled fraud at scale; methamphetamine production and opium cultivation have resurged; and hundreds of thousands of people have been trafficked into forced criminality. This article synthesises the most authoritative recent evidence on this transformation, situates it within international relations theory on state weakness, state capture, and transnational crime policing, and traces the political–economic feedback loops that bind illicit markets to domestic governance and great‑power influence. It concludes with policy options grounded in recent enforcement innovations (e.g., FinCEN’s Section 311 rule and coordinated sanctions) and proposes a research agenda for scholars of IR, political economy, and cybercrime.

1. Introduction: Cinema’s myth, the Mekong’s reality

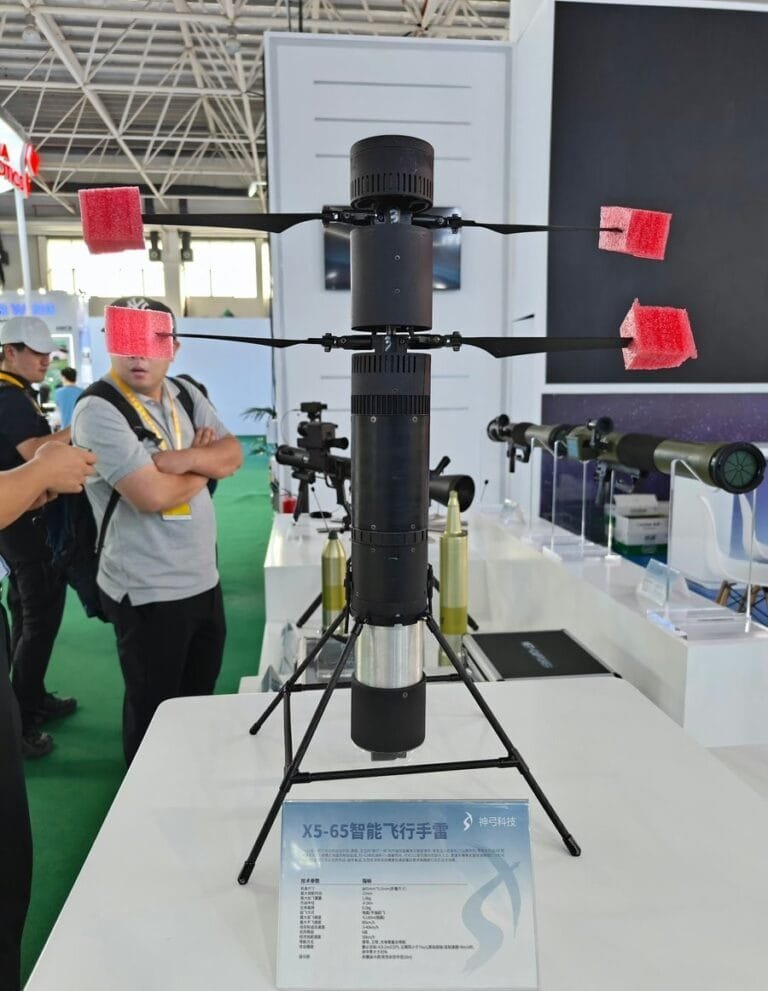

The criminal governance that dominates parts of the Mekong today is not the aestheticised underworld of yakuza melodrama. It is a logistics business: purpose‑built compounds ringed by razor wire; dormitories and “phone farms” with thousands of handsets; data‑driven scripts; satellite terminals; stablecoin rails; and escrow marketplaces. UN and rights‑body reporting since 2023 documents “hundreds of thousands” of people trafficked into these compounds (particularly in Myanmar and Cambodia) to conduct long‑con “pig‑butchering” investment scams and related frauds, under threat of violence and debt bondage. (unognewsroom.org)

The parallel expansion of synthetic-drug production in Myanmar’s Shan State (the historic Golden Triangle) has created an illicit dual economy: methamphetamine revenues estimated at US$30–61 billion annually across East and Southeast Asia, and cyber-fraud proceeds amounting to tens of billions globally. Recent research by the United States Institute of Peace estimates that scams operated from Mekong-based compounds stole approximately US$43.8 billion in 2023 alone, a figure equivalent to nearly 40 percent of the combined formal GDP of Myanmar, Cambodia, and Laos. (usip.org)

2. Concepts and literature: State weakness, state capture, and criminogenic asymmetries

Three strands of IR/state‑crime scholarship help explain the Mekong’s divergence:

- State weakness and violent pluralism. In Myanmar, long civil wars left de facto autonomous zones in borderlands where armed groups—both anti‑junta and pro‑junta militias—tax, protect, or directly run drug labs and scam infrastructure. ICG’s foundational analysis of Shan State describes how illicit rents entrench conflict and governance failure. (ecoi.net)

- State capture and protection economies. In Cambodia and Laos, licit megaprojects (casinos, SEZs, real estate) and political patronage intertwine with illicit finance. The Golden Triangle SEZ (GTSEZ) in Laos exemplifies enclave governance: a 99‑year concession dominated by the King’s Romans group, where Lao authorities have had limited access and have even required permission to enter—a pattern consistent with “protection markets” in the comparative literature. (rfa.org)

- Criminogenic asymmetries in finance and technology. UNODC’s 2024 technical brief shows how under‑regulated online gambling, junkets, and stablecoin‑based underground banking “supercharged” illicit economies; decentralised platforms allow layering and commingling at scale, while escrow markets on Telegram industrialise the sale of scam tooling and laundering services. (scribd.com)

3. A political economy timeline: From Macau’s junkets to Mekong compounds

2012–2019: Anti‑corruption in China and the Macau junket shock. Xi Jinping’s crackdown narrowed the space for VIP gambling and junkets; Suncity’s Alvin Chau was arrested in 2021 and sentenced in 2023, signalling a secular decline in the old Macau model. Networks with triad linkages pivoted to Southeast Asian locales with permissive governance and a ready market of Chinese gamblers online. UNODC officials have emphasised how the junket crackdown displaced darker operations into the Mekong. (apnews.com)

2017–2020: SEZs and casinos as conduits. In 2018, the U.S. Treasury designated the “Zhao Wei Transnational Criminal Organisation,” centred on Laos’s GTSEZ and the King’s Romans casino, for drug trafficking, money laundering, and human and wildlife trafficking—an early, public signal of criminal state capture risks in enclave economies. (home.treasury.gov)

2020–2022: COVID‑19 and the pivot to “fraud factories.” With physical gambling constrained, underused casinos and hotels were fortified into scam compounds. OHCHR in 2023 reported at least 120,000 trafficked into forced criminality in Myanmar and about 100,000 in Cambodia, with operations radiating across the region. (ungeneva.org)

2023–2025: Industrialisation, export, and fledgling pushback. UNODC and allied research estimate tens of billions in annual scam losses, with AI‑enabled scripts and deepfakes accelerating the “scamdemic.” The U.S. and U.K. intensified sanctions and AML actions; FinCEN in 2025 cut Cambodia‑based Huione Group off from the U.S. financial system under USA PATRIOT Act §311, citing its role as a laundering node for Southeast Asian TCOs and even DPRK cyber‑heists. (fincen.gov)

4. Case studies

4.1 Laos: The GTSEZ and enclave criminal governance

The Golden Triangle SEZ in Bokeo province operates under a 99‑year lease; media and rights monitors have long documented that Lao police access is constrained by zone authorities and that the state holds a minority (20%) stake—features that, in practice, produced a permissive environment for trafficking, online gambling, and laundering. The U.S. Treasury’s 2018 designation of the Zhao Wei network formally tied the zone to multi‑commodity crime (drugs, humans, wildlife) and money laundering through casino infrastructure. (rfa.org)

4.2 Cambodia: Corporate facades, laundering rails, and forced-labour compounds

Two enforcement actions in 2025 reframed the landscape.

- FinCEN’s final §311 rule against Huione Group (Oct 14, 2025) severed the conglomerate’s access to U.S. correspondent banking, after a May finding alleged billions in laundering and facilitation of “pig‑butchering” flows via Telegram‑based escrow markets and Huione‑affiliated payments channels. Reuters and Elliptic’s open‑source work documented the takedown of “Huione Guarantee” on Telegram and its role as an illicit bazaar offering laundering, data, infrastructure, and even “detention equipment” used in compounds. (fincen.gov)

- On October 14–17, 2025, the U.S. unsealed an indictment against Chen Zhi, chairman of Prince Holding Group, alleging he directed forced-labour scam compounds in Cambodia that generated billions in fraud and laundered proceeds via complex crypto techniques; Treasury simultaneously designated the “Prince Group TCO,” and U.K. authorities issued complementary sanctions. These are allegations to be proven in court, but the charging documents and parallel sanctions detail compound‑level ledgers, “phone farms,” and the use of violence to coerce trafficked workers. (justice.gov)

More broadly, Amnesty has argued that Cambodia’s crackdowns have been uneven, with systemic failures to protect victims and disrupt ownership/control networks; Cambodian authorities counter that thousands of arrests and deportations since mid‑2025 show seriousness. (reuters.com)

4.3 Myanmar: War economies, armed protection, and selective crackdowns

Shwe Kokko’s Yatai “New City” project in Kayin State epitomises the fusion of real estate, militia power (Karen BGF), online gambling, and scam compounds; the Chinese‑Cambodian tycoon She Zhijiang—arrested in Bangkok in 2022—is now set for extradition to China after appeals were exhausted in November 2025. (apnews.com)

In October 2025, Myanmar’s junta announced a high‑profile raid at KK Park near Myawaddy, detaining over 2,000 and seizing Starlink terminals, while parallel reporting and OSINT showed thousands fleeing and SpaceX disabling more than 2,500 devices across scam centres. Whether the raid marks structural change or mere displacement remains contested. (apnews.com)

Meanwhile, China’s posture has been two‑handed: it has facilitated major repatriations and secured severe sentences—including multiple death sentences in September 2025—against Kokang‑based scam bosses; but analysts warn that Beijing’s expanding police presence and sub‑regional mechanisms (e.g., the Lancang‑Mekong Law Enforcement and Security Cooperation Center) also consolidate influence, creating incentives for “selective enforcement.” (washingtonpost.com)

5. Money laundering, rails, and escrow platforms

UNODC’s 2024 brief maps how casinos (brick‑and‑mortar and online), junkets, underground banking, and stablecoins form a modular laundering stack for scam and drug proceeds. The ascent of USDT as an underground banking instrument has been particularly important: cases in 2023–2025 show freezes and seizures of hundreds of millions coordinated by issuers (Tether), exchanges, and law enforcement, indicating both the scale of illicit use and the feasibility of targeted disruption when counterparties cooperate. (scribd.com)

Escrow‑style Telegram markets operationalise this stack. After a 2025 purge, Telegram removed Huione‑ and Xinbi‑branded “guarantee” channels that, according to Reuters and Wired’s synthesis of blockchain analytics, had processed tens of billions of dollars by brokering laundering services, SIMs/accounts, social engineering kits, deepfake content, and coercive tools. (reuters.com)

6. Drugs, scams, and the “hybrid illicit economy”

The methamphetamine economy centred in Myanmar’s Shan State—long documented by ICG and UNODC—has reached record seizure levels since 2023–2024, with AP and UNODC noting profits “in the billions.” The meth market’s size (UNODC’s long‑standing 30–30–30–61 billion range for East/Southeast Asia and Oceania) now intersects with cyber‑fraud finance and enclave governance, creating diversified revenue streams for armed actors and their protectors. (apnews.com)

UN reports also record Myanmar’s resurgence as the world’s leading opium cultivator in 2023, underscoring the substitution/complementarity between opiates and synthetics within war economies. (ungeneva.org)

7. Human security and international law: Forced criminality

The signature human‑rights harm of the “scam state” is not just the financial loss to victims abroad; it is the systematic trafficking of workers into forced criminality inside compounds. OHCHR’s 2023 assessment—corroborated by subsequent reporting—documents torture, sexual violence, confinement, and debt bondage, and urges a victim-centred approach that distinguishes those coerced into crime from culpable perpetrators. (ungeneva.org)

8. Geopolitics and transnational policing

For IR scholars, the Mekong’s criminal transformation has re-territorialised Chinese security and influence in Southeast Asia. Beijing’s push for crackdowns in Myanmar and Laos, bilateral coordination centres (e.g., in Bangkok/Mae Sot), and extraterritorial policing controversies (“overseas police stations”) have all sparked debate: is law‑enforcement cooperation neutral capacity‑building, or a channel for coercive leverage and selective impunity? The balance of evidence suggests both dynamics are present—simultaneously heightening enforcement and entrenching Chinese state presence. (reuters.com)

9. Why states allow this: Institutional weakness, rents, and international constraints

- Political rent‑seeking and fiscal desperation. Elites in fragile states monetise SEZ concessions, casinos, and real estate in exchange for investment and informal payments. Laos’s GTSEZ revenue sharing and political protection are textbook examples. (rfa.org)

- Security externalities. In Myanmar, the junta and proxy militias fund counterinsurgency through illicit economies; in contested areas, multiple armed actors extract rents, making any single‑agency enforcement fragile or performative. (ecoi.net)

- AML/CTF capacity gaps and regulatory arbitrage. FATF lists illustrate differential pressure: Myanmar remains on FATF’s call‑for‑action list; Laos re‑entered FATF’s “increased monitoring” in 2025; Cambodia exited the grey list in 2023 but faces ongoing scrutiny via targeted U.S./U.K. actions. Criminal networks exploit these asymmetries. (fatf-gafi.org)

10. Policy options: What works, what doesn’t

The last two years provide proof‑of‑concept interventions that merit scaling:

- Use systemic AML tools against keystone nodes. FinCEN’s §311 action against Huione Group and the parallel crackdown on Telegram escrow markets show that removing access to correspondent banking and major platforms can degrade capacity across multiple compounds at once. (fincen.gov)

- Pair sanctions with criminal process. The October 2025 DOJ indictment of Prince Holding Group’s chairman, paired with OFAC and U.K. sanctions, demonstrates how criminal charging, asset forfeiture (the U.S. announced custody of ~127,000 BTC, the largest such action to date), and sanctions can be mutually reinforcing, even when defendants are abroad. Ensure victim compensation pathways are pre‑planned. (justice.gov)

- Treat forced criminality as trafficking. Align prosecutorial guidance and immigration protection so trafficked workers are screened in, not summarily prosecuted or deported; resource cross‑border victim services through ASEAN and the UN system. (ungeneva.org)

- Harden on‑ramps and off‑ramps. Expand stablecoin issuer/exchange MOUs, red‑flag typologies, and automated freezes with due process; extend telecom and app‑store accountability for escrow and “guarantee” services facilitating laundering and trafficking. Evidence from Tether/OKX/Binance freezes (>225Minonecase; 225M in one case; ~225Minonecase; 50M in another) suggests impact is real when firms and LEAs coordinate early. (benzinga.com)

- Reform SEZ governance. Require treaty‑anchored police and prosecutorial access inside SEZs; sunset concessions that condition state entry on operator permission; mandate beneficial‑ownership disclosure for SEZ licensees. The GTSEZ experience shows that “sovereignty holidays” become magnets for multi‑commodity crime. (rfa.org)

- Push FATF‑consistent remediation. Tie infrastructure and development finance to AML/CTF benchmarks; help Laos execute its new FATF action plan; keep Myanmar under enhanced due diligence while carving out humanitarian channels to avoid de‑risking that harms civil society. (fatf-gafi.org)

- Build an ASEAN–Mekong cyber‑fraud compact. Scale joint task forces (with Thailand as a hub) to disrupt compounds, protect victims crossing into Mae Sot, and coordinate evidence/intelligence sharing with U.S., EU, Japan, Australia, and Interpol. (reuters.com)

11. Research agenda

- Governance of escrow markets. Telegram “guarantee” ecosystems industrialise cyber‑fraud. How do different platform governance regimes (EU DSA, U.S. Section 230 reform proposals) alter network resilience?

- Illicit–licit capital interpenetration. Disentangle how scam and drug proceeds enter real estate, logistics, and fintech in Singapore, Hong Kong, Dubai, London, and North America; develop forensic proxies for risk screening, building on USIP and UNODC analytics. (usip.org)

- Transnational policing and sovereignty. Evaluate the net effects of China’s law‑enforcement expansion (LM‑LECC, bilateral centres, “persuasion to return”) on crime reduction versus political leverage in ASEAN states. (strategicspace.nbr.org)

12. Conclusion

Mainland Southeast Asia’s illicit economies have been reorganised around digital crime and enclave governance. The “scam state” thrives where weak institutions, rent‑seeking, armed protection, and permissive financial rails meet. Yet 2024–2025 also show that systemic tools—coordinated sanctions, §311 designations, platform‑level purges, and large crypto forfeitures—can bend the curve when victim-centred approaches and multilateral policing are sustained. For scholars, the Mekong has become a crucial laboratory for studying how illicit markets reshape sovereignty and great‑power competition; for policymakers, it is a test of whether twenty‑first‑century financial governance can keep pace with twenty‑first‑century criminal innovation.

Acknowledgement of allegations and dates

- Allegations referenced in U.S. indictments (e.g., against Prince Holding Group’s chairman, unsealed October 14, 2025) remain to be adjudicated in court. (justice.gov)

- All dates are given in the Gregorian calendar; the current analysis reflects sources available through November 11, 2025.

Selected sources

- United States Institute of Peace (Senior Study Group), Transnational Crime in Southeast Asia: A Growing Threat to Global Peace and Security, May 13, 2024 (quantifies ~$43.8B annual scam thefts; links to elites; country cases). (usip.org)

- UN Office on Drugs and Crime (2024), Casinos, Money Laundering, Underground Banking… (technical policy brief; digital rails and casinos). (scribd.com)

- OHCHR/UN Geneva (Aug 29, 2023), Hundreds of thousands trafficked into online criminality (baseline forced‑criminality estimates). (ungeneva.org)

- FATF/FinCEN notices (2024–2025) on Myanmar (call‑for‑action) and Laos (increased monitoring), and FinCEN’s Huione §311 Final Rule (Oct 14–15, 2025). (fatf-gafi.org)

- U.S. Treasury OFAC (Jan 30, 2018), sanctions on the Zhao Wei TCO (GTSEZ/King’s Romans). (home.treasury.gov)

- DOJ/US OPA (Oct 14–17, 2025), indictment of Prince Group’s chairman; parallel U.S./U.K. sanctions and massive bitcoin forfeiture action. (justice.gov)

- Reuters/AP/Wired on Huione Guarantee takedowns, Telegram purges, and laundering markets; Tether/OKX/Binance freezes (2023–2025). (reuters.com)

- International Crisis Group (Jan 8, 2019), Fire and Ice: Conflict and Drugs in Myanmar’s Shan State (drug–conflict nexus). (ecoi.net)

- AP/Reuters/Myanmar Witness/AGBrief on the October 2025 KK Park raid and Starlink disruptions. (apnews.com)

- UNODC/Reuters/AP on methamphetamine market size and record seizures (2019–2024). (taipeitimes.com)

Notes on contested claims and nomenclature

- Corporate and individual linkages (e.g., board roles, political advising) are reported by major outlets or official filings; where material is under legal dispute, this essay cites mainstream reporting or official notices and avoids uncorroborated assertions. (washingtonpost.com)

- “Pig‑butchering” is used as a term of art in law enforcement and analytical reporting to denote long‑con investment frauds.

Policy one‑pager (for practitioners)

- Target nodes, not just sites: Use §311‑style measures and Magnitsky‑style sanctions against conglomerates, escrow platforms, and offline service providers that give compounds “two legs”—finance and labour.

- Make victim-centred triage the default: presume trafficking where indicia of coercion exist; fund protection and repatriation through seized‑asset pools.

- Force SEZ governance upgrades: unconditional law‑enforcement access; BO disclosure; third‑party audits; concession clawbacks for non‑compliance.

- Institutionalise crypto cooperation: formal MOUs with issuers/exchanges; shared typologies; rapid‑freeze lanes with judicial oversight.

- Multilateralize policing while guarding sovereignty: ASEAN‑anchored task forces with transparent mandates; independent monitoring to mitigate selective enforcement risks. (reuters.com)

If you’ve read this far and would like, I can adapt this into a shorter policy brief (2–3 pages) with a visual map of key nodes and recommended sequencing for sanctions/AML actions. Let me know if you’d like me to do that!

What are your thoughts about this? Let me know in the comments!

Learn more:

- Hundreds of thousands trafficked into online criminality across SE Asia | The United Nations Office at Geneva

- Transnational Crime in Southeast Asia: A Growing Threat to Global Peace and Security | United States Institute of Peace

- International Crisis Group (Author): “Fire and Ice: Conflict and Drugs in Myanmar’s Shan State”, Document #1456625 – ecoi.net

- Lao authorities seem powerless to stop crime in Golden Triangle economic zone – Radio Free Asia

- Casino Underground Banking Report 2024 | PDF | Organized Crime | Cryptocurrency

- Macao jails Suncity founder 18 years over illegal gambling

- Treasury Sanctions the Zhao Wei Transnational Criminal Organization | U.S. Department of the Treasury

- FinCEN Issues Final Rule Severing Huione Group from the U.S. Financial System | FinCEN.gov

- Office of Public Affairs | Chairman of Prince Group Indicted for Operating Cambodian Forced Labor Scam Compounds Engaged in Cryptocurrency Fraud Schemes | United States Department of Justice

- Amnesty says Cambodia is enabling brutal scam industry

- Thailand court orders extradition to China of alleged online gambling kingpin

- Myanmar military shuts down a major cybercrime center and detains over 2,000 people

- China sentences 11 criminal gang leaders to death for scam operations

- 2 massive black market services blocked by Telegram, messaging app says

- East, Southeast Asia had record methamphetamine seizures last year. Profits remain in the billions

- Myanmar overtakes Afghanistan as world’s top opium producer | The United Nations Office at Geneva

- Thailand and China to set up coordination centre to combat scam call networks

- High-Risk Jurisdictions subject to a Call for Action – 24 October 2025

- Tether, OKX Strike At ‘Pig Butchering’ Scam With $225M Freeze – Benzinga

- High-Risk Jurisdictions subject to a Call for Action – 21 February 2025

- Policing Beyond Borders: China’s Law-Enforcement Expansion in the Mekong Region – Mapping China’s Strategic Space

- UN warns on Asian meth trade – Taipei Times

- How one cyberscamming syndicate used Singapore for legitimacy

Avi is a researcher educated at the University of Cambridge, specialising in the intersection of AI Ethics and International Law. Recognised by the United Nations for his work on autonomous systems, he translates technical complexity into actionable global policy. His research provides a strategic bridge between machine learning architecture and international governance.